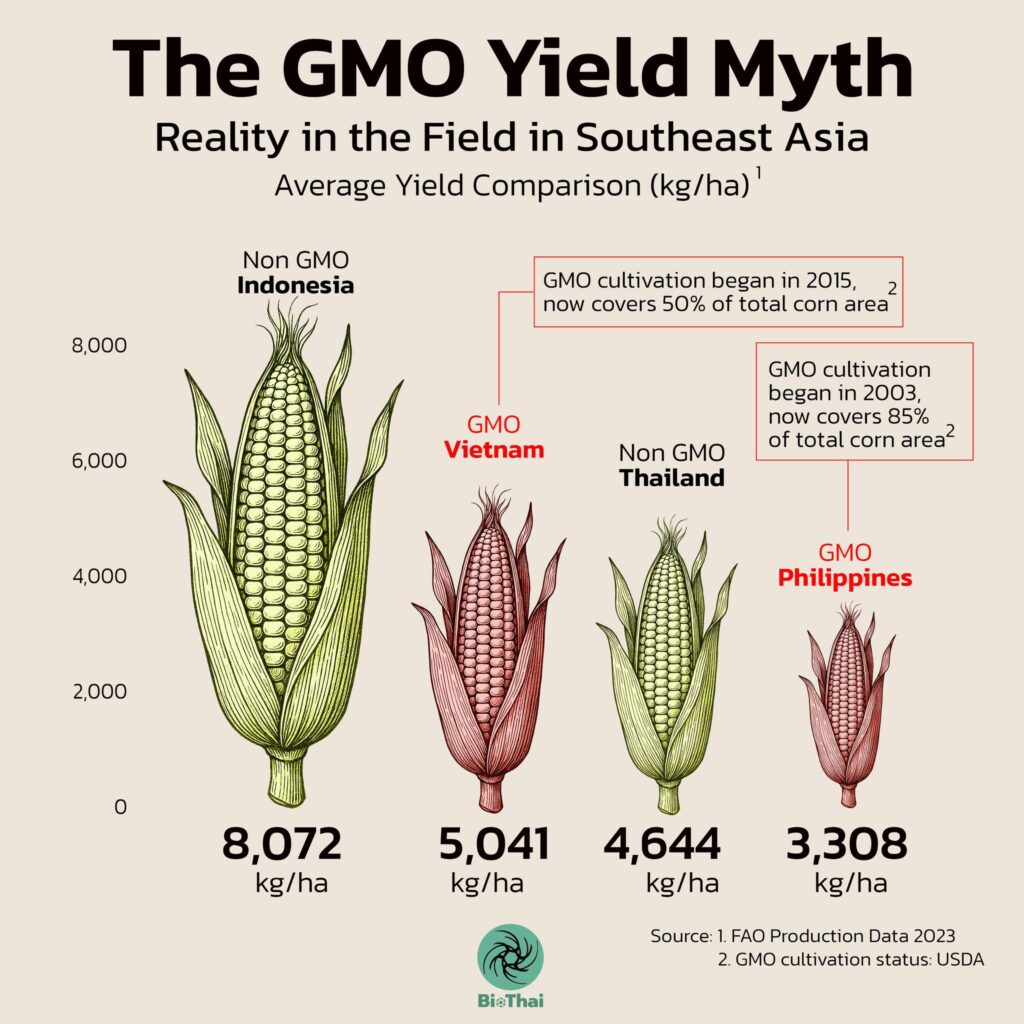

Thailand and Indonesia grow conventional hybrid corn, while the Philippines and Vietnam have allowed the cultivation of genetically modified (GMO) corn.

When comparing the FAO data average yields per hectare, it becomes clear that the Philippines, which began planting GMO corn in 2003 and now grows GMO varieties on more than 85% of its total corn area, still records an average yield of only 3,308 kg/ha. This is more than 40% lower than Thailand, which does not allow GMO cultivation.

Similarly, Vietnam, where the government approved GMO cultivation in 2013 and now plants GMO corn on 50% of its total corn area, has an average yield of 5,041 kg/ha. This is comparable to Thailand’s yield (4,644 kg/ha), not counting Thai farmers in certain areas who achieve significantly higher yields. Notably, Indonesia, which grows only non-GMO corn, outperforms all with an average yield of 8,072 kg/ha!

GMO crops were not developed to increase yields per hectare—yields are largely determined by overall farm management. Instead, GMOs were created to address specific issues, such as making it easier to apply herbicides through engineered resistance to chemical weedkillers.

We raise this point to challenge the common misconception that Thailand’s inability to compete with the United States in corn production is because we do not grow GMO crops. Some argue that in order for Thai farmers to compete, the government must approve GMO cultivation. This narrative is a corporate trap promoted by companies seeking to sell expensive seeds bundled with proprietary herbicides. (GMO corn seeds typically cost twice as much as conventional hybrid seeds.)

We should not compare U.S. corn yields with Thailand’s and then conclude that the key difference is GMO seeds. The U.S. industrial farming system, based on vast monoculture fields, heavy machinery, chemical inputs, and generous government subsidies, is entirely different from the ecological and economic conditions of Southeast Asia.

A more appropriate and meaningful comparison is among smallholder farmers in similar agro-ecological zones, such as between Thailand, the Philippines, Indonesia, and Vietnam. This provides a much clearer and more realistic picture of the situation.

Two decades ago, Thailand once led the region in average corn yields due to strong research and development. However, yields have since stagnated or even declined in some years. This is largely due to neglected R&D, the promotion of corn cultivation in unsuitable areas, and most importantly, a lack of attention to sustainable agriculture, particularly soil fertility and ecological health.