1. The Political and Economic Crisis

This year, our annual conference was organised at a time in which our country faced a not very normal situation, as right now we are in a democratic crisis. This crisis is linked to economic problems, which create a stomach ache for people all over Thai society both over the short-term and long-term.

Several Western governments have opposed the military coup, cutting off assistance and military relationship to the point that they have refused to sign economic cooperation agreements. At the same time, Thailand is facing very major problems, for example its GSP rights are being cut, which allow certain sectors of industry to export goods to Europe at low rates of tax, and there is growing opposition to the Thai food industry that is linked to human trafficking. All these overwhelming problems have occurred simultaneously.

2. Are we ready to address the political and economic crisis?

We have to analyse the current political and economic crisis carefully and comprehensively, without rushing to oppose the position of the Western nations. At the same time, we shouldn’t fall into the trap of wanting to please the West or any other country. But we must get them to accept the status of the political system as it currently is. As FTA Watch has warned, the liberalisation of trade and the acceptance of Western trade rules have often had a serious impact on ordinary people. It has happened many times in the past when there was a military coup government, for example the amendment of the law on medicinal patents to please the US government and the cancellation of tax on agrochemicals to please the foreign agrichemical companies, during the time of the 1992 military government, and the signature of JTEPA, which opened the way for bringing in waste products from Japan to be discarded in Thailand, during the time of the last military government in 2006.

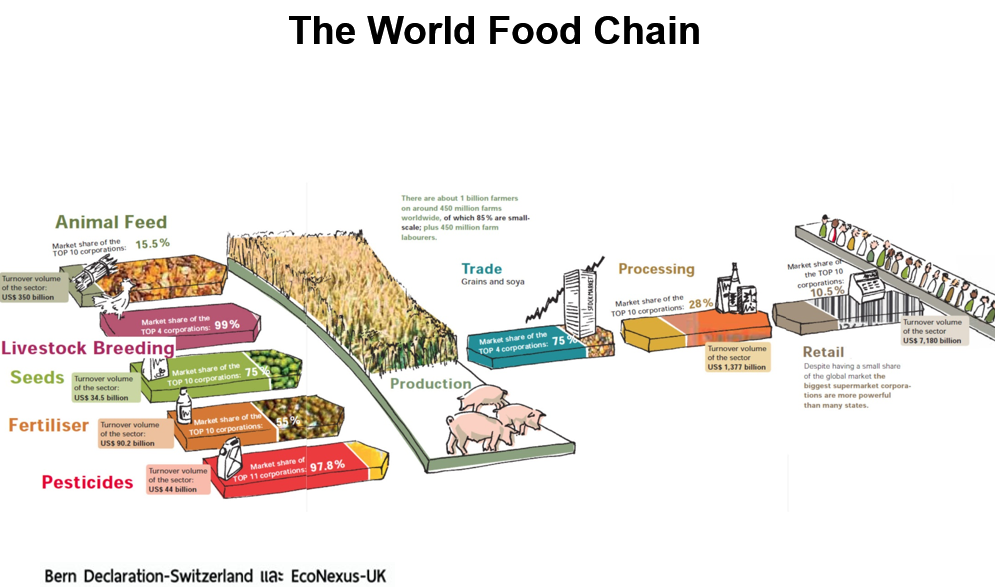

I call on those who support the military junta and those who distrust them to together press the government so that they do not bring into law the UPOV Convention 1991, or the extension of patent rights over medicines, nor give in on the cultivation of GM crops over which transnational corporations have a monopoly all over the world. Each of these will have an impact on biodiversity, farmers, and everyone who needs to access medicines.

3. Criticism of the food industry is not a trade barrier, and human trafficking is not the only problem

The issue of human trafficking in the shrimp industry/food industry, raised by the European media and the US government, will be a valuable lesson for the Charoen Phokpand company and the country as a whole. Charoen Phokpand has become a giant global producer of animal feed, overtaking Tyson Foods, Cargil Brazil Foods, Hunan etc. It also controls the largest share of the convenience store market, it controls the hypermarket, Makro, which has a massive impact on traditional corner stores, and controls over half the market for maize and vegetables seeds. All of this means that its actions are being investigated more carefully.

If we don’t focus only on “national benefits” or “trade barriers”, as certain groups tend to do, most of us might support the actions of the Western countries, since human trafficking is incontrovertibly an abuse of trade ethics.

However there are also other important issues at stake, such as:

1. The problem of human trafficking is not the only question of ethics of the food industry. The food industry must ask itself questions or sort out its problems, such as the problems of

- using destructive fishing gear,

- its sales tactics for selling seeds,

- buying from farms which have encroached onto watershed areas

- inequality in the contract farming system

- bullying independent seed enterprises and private sector operators, small-scale traders

- the centralization of food distribution system etc.

2. The push to sort out ethical problems in the food industry has not come so much from the government, but mostly from the efforts of consumers and the exercise of their power to choose. This case is similar to the opposition to GM foods of the consumer movement in Europe. It puts pressure on the retail warehouses, shops, etc until the government has to put in place strong measures, such as labelling GM foods

On one side, this is a good opportunity for the food industry to pinpoint where these problems lie and sort them out, and is a warning of the problems which lie in store in the future for them. And on the other hand, this issue can tell consumers and Thai society that we can do something ourselves to build a food democracy and demand corporate ethics.

4. Food Security is Food Democracy

When we see things comprehensively from the perspective of food security, people may have access to sufficient quantity of food but this is not enough without considering whether the food production process destroys the environment, or comes from a production monopoly, or comes from production relations which in which small-scale farmers have to take this greatest risks share of the risks, or comes from a centralised food distribution monopoly. This is not acceptable. Because in the end such a food system is neither secure nor sustainable. It has been found that as the food industry grows, the small-scale farming sector is suppressed. Many countries have started to experience problems of lack of variation in their diet, and lack of food safety, whether its as a result of mono-crop farming or the use of genetically engineered species in agriculture, or other reasons.

Real food security is having food democracy. Or where all the people, both farmers and consumers have the power to determine the food system that they require. They do not leave a single power over the food system to be dominated by anyone, so that everyone can have sufficient food to eat, that is nutritious, safe, diverse and appropriate to the culture, sustainable and addresses the various crises over the long term.

5. Food democracy over the food system

- farmers must have land, and land must belong to the tillers. And we must not accept that any member of the private sector can hold hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of rai, as we are seeing today. We should not let the discourse of “large-scale landowners produce more food by using monocrop production technologies” to be our standard of measurement. The diversity of production in a tropical ecosystem of small-scale farmers, on the contrary, are more efficient.

- seeds should be in the hands of the small-scale farmers. We should not allow the use of laws to bully farmers who produce their own animal feed, and raise a variety of livestock. Having a variety of proteins is very important and should be developed.

- it’s surprising that so many government institutions have been converting themselves into a part of the efforts to support the role of the large-scale private sector instead of supporting the small-scale farmers or the community enterprises. How can we get government institutions to return to their duty to address the needs of the public?

- has the food distribution system under modern trade increased the availability of diverse food? Or to put it another way, can we build an alternative food distribution system such as, the Pukpinto Khaaw Network and the Puean Pluk Puea Kin Group farming to eat are currently doing? How can we prevent these local markets from being replaced by modern trade, where we can easily find raspberries, plums, cherries but not kratin shoots, sadao, khae and mieng leaves.

- the role of women which are the seed harvesters, they manage and prepare the food in the household, and manage the largest share of the household economy, and control the food costs, have had their role decimated, as more and more people rely on convenience stores. It’s a pity that we hardly talk about these issues at all.

6. Food Security issues/ food sovereignty has given additional meaning to the term “democracy”, which is about giving power to families, women and consumers.

An old friend of mine, Samart Sakawi, told me that the issue and understanding of food democracy/food security, gives greater power to women and children families and the elderly, small-scale farmers, consumers, local communities. We can listen to this issue in his lectures and stories from his work of over 30 years with communities. We will hear his words on rising up to use the power of people in different groups in different contexts related to food. Over the next two days of this meeting, we will hear from experience in Chiang Mai, Yasothorn, Surin, Songkhla, as well as in initiating new models of relationships in the food system. At the same time, I believe that these issues can provide us with the tools to build a greater, more real, democracy at the central level too. We have seen that, in the countries which export and advertise democracy and human rights such as the United States, small-scale farmers and American consumers have to fight for real democracy also. Last year in May, 1 million Americans walked on a march to oppose the large scale food industry demanding the “right to know”. One of the points they make is that more than 80% of Americans support the GM labeling, however the American government still refuses to order this because of the influence of the food corporations.

If we take “democracy in food matters” to be a criteria by which to measure the level of democracy in Thai society over the last few decades, we might ask ourselves what little or great things can we do during this period of political crisis?